El mayor fallo del modelo de privatizaciones thatcheristas

FERNANDO GUALDONI. EL PAIS. Madrid 19 JUL 2002

Railtrack se formó de la privatización de la compañía pública British Rail en 1996. El ferrocarril británico, al igual que el servicio postal, era uno de esos servicios que los británicos jamás hubiesen imaginado ver en manos privadas. Después de todo, el ferrocarril británico es el más antiguo del mundo, las primeras vías se pusieron en 1604. La venta de British Rail fue la última de la serie de grandes privatizaciones iniciadas por Margaret Thatcher. La hizo el primer ministro conservador John Major, predecesor del laborista Tony Blair.

El nacimiento de Railtrack supuso todo un acontecimiento en Londres. La oferta pública de acciones fue un éxito, y cómo no iba a serlo si la compañía que salía a Bolsa contaba con una infraestructura de 32.200 kilómetros, 2.500 estaciones y miles de cruces, túneles, puentes y viaductos. Los ingresos de la compañía proceden de la facturación que hace a unas 25 compañías de transporte de pasajeros y carga por ferrocarril. Los servicios de Railtrack van desde la coordinación de los trenes hasta la limpieza de los aseos en las estaciones. Toda la gestión y el mantenimiento de la red están en manos de esta empresa.

Graves accidentes

Dos años después de la privatización, Railtrack comenzó a tener problemas. En 1998, el Gobierno recibió las quejas de los usuarios por los retrasos y un año después dos trágicos accidentes (uno que se saldó con 31 muertos y el otro con siete) hicieron saltar todas las alarmas del Ejecutivo. La empresa intentó aplacar la ira del Gobierno y los usuarios con el anuncio de una inversión de unos 4.000 millones de euros para mejorar el funcionamiento y la seguridad de la red. No obstante, otro fatal accidente a finales de 2000 terminó por hundir la compañía y apresuró la salida de su presidente, Gerald Corbett.

El Gobierno laborista forzó a Railtrack a reducir servicio hasta que se hiciera una inspección y reforma de la red para que fuese más segura. Ya en 2001, la empresa solicitó al Gobierno ayuda financiera y éste se la negó. Fue entonces cuando la Administración de Blair decidió tomar el control de la empresa y suspender su cotización en Bolsa. Durante ocho meses, funcionarios se hicieron cargo de vigilar la gestión de Railtrack hasta que se completara el proceso de reconversión de la compañía.

La empresa volvió a cotizar y, en lo que va de año, David Harding reemplazó a Steve Marshall al frente del grupo y, bajo la gestión del primero, se acordó la venta a Network Rail.

http://elpais.com/diario/2002/07/19/economia/1027029603_850215.html

ANTECEDENTES

Desmembrada y descarrilada: la desafortunada privatización de “British Rail”

02-07-11 . Tim Engartner, “Freitag”, nº50/2007 “Isla de las catástrofes” o “Perdidos en la competencia” – de esta forma se expresan los periódicos de la isla, cuando dedican sus primeras paginas al tema de la privatización de British Rail. […] el gobierno conservador de John Major había hecho todo lo posible para maximizar los beneficios de la […]

McKinsey & Co. le diseñó a Fomento la privatización de los trenes españoles

EL MUNDO / Domingo 17 de octubre de 1999. Renfe no quiere perder el tren. JULIAN GONZALEZ Miguel Corsini, actual presidente de Renfe, quiere pasar a la historia como el hombre que preparó la compañía para el nuevo milenio. El reto es peliagudo, porque si fracasa en el intento la empresa ferroviaria puede descarrilar y […]

TIME TO RENATIONALISE THE RAILWAYS

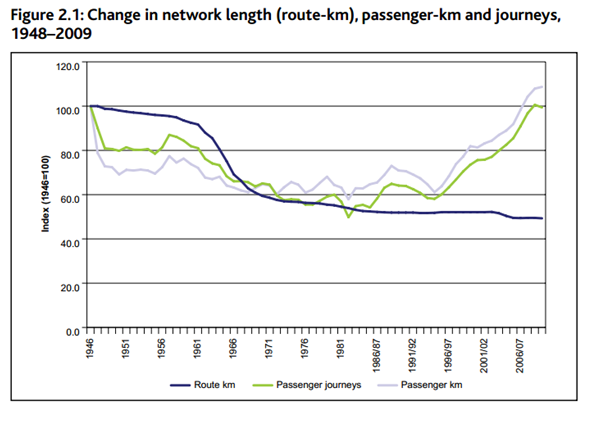

Rail is back on the agenda in Britain. An average of 3.3 million people get on a train every day- and the number is growing, fast. The UK’s rail infrastructure is far behind that of continental Europe, with just 60km of high-speed line, compared to 3480km across the continent. HS2 will begin to change this. Meanwhile, the Coalition, desperate to appear proactive on the economy, is promising the “‘biggest investment’ since the Victorians” in Britain’s beleaguered railway network, involving some £10bn in capital investment.

But the ownership of the railways is also coming into question. Rail fares have sky-rocketed far faster than inflation, even as the rail network sees ever greater use. The Labour Party’s Shadow Transport Secretary, Maria Eagle has begun (very quietly and cautiously) to begin talking about nationalisation once again. Meanwhile, groups on both the left and right, not least the Adam Smith Institute, whose ideas inspired the 1990s privatisation of British Rail, universally accept that Britain’s railway privatisation has been a disaster, even though they disagree sharply about the way forward.

With the political climate turning against the idea of private corporations running public services, and the rail network becoming ever more crucial to our economy, it seems a good time to reopen the debate about who owns Britain’s railways.

Has Privatisation Failed?

When the Major government privatised British Rail in the 1990s, it has high hopes. The railways would be removed from the political influence, and all the associated mishandling, competition would lower fare prices, efficiency would improve, the need for expensive taxpayer subsidies would fall, and safety standards would improve. Of these, only the latter has actually happened: safety has improved. Every other aim has failed, something agreed by experts and commentators from across the political spectrum.

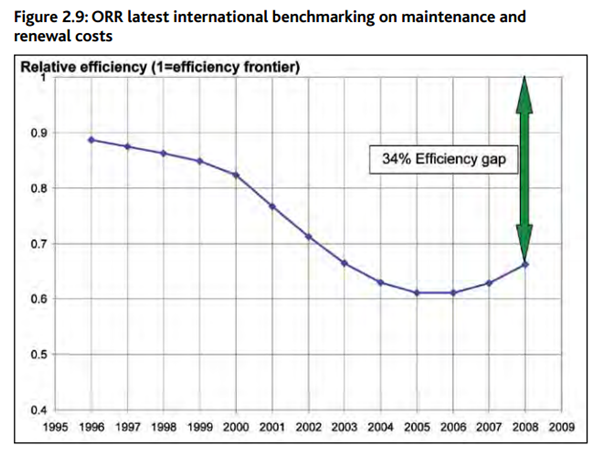

In the period before nationalisation, British Rail was indisputably one of the most efficient railway operators in Europe. After privatisation, the new operators found that British Rail had already done much of what could be done to improve efficiency: there were not many cost savings that could be made. But in fact, the railways have become less efficient since privatisation. The McNulty report in 2011 found “an efficiency gap of 34% between British railways and top performing European infrastructure providers”. The gap that has widened dramatically since privatisation, McNulty concluding, “The trend since privatisation is shown… indicating a rapid decline in relative efficiency during the Railtrack period, a stablilising of the position by 2005/06 and a gradual recovery since then”. Meanwhile the Just Economics think-tank found that Britain’s railways were the least efficient in Europe.

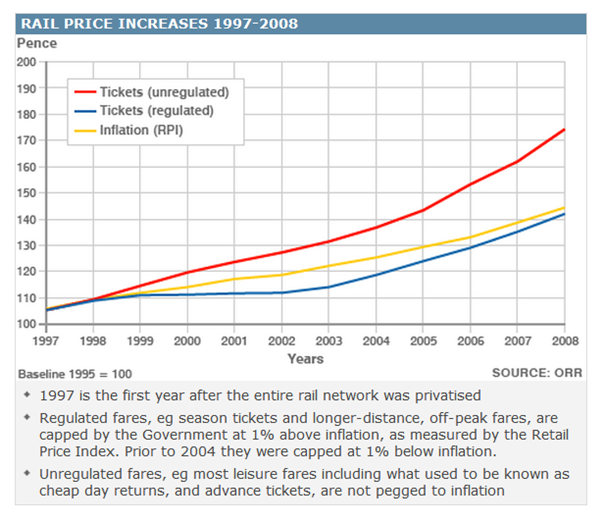

The number of users of British Rail has greatly increased– rail is becoming ever more important to the UK economy. Indeed Britain’s rail system is now seeing as much use as it did in the late 1940s, before most families owned a car. But this has not brought fares down. British Rail fares are now the highest in Western Europe. This year, fares have already risen 5.9%, with some commuters seeing an 11% increase. Indeed, the recent government investment plans are likely to accompany fare rises far above inflation. In fact, since privatisation, all fares, except those directly capped by the government, have risen consistently above inflation. The result is that even as Britain’s railways are becoming more important to the economy, they are becoming less affordable to ordinary people. Even Conservative Transport secretary has admitted that rail is becoming “a rich man’s toy”.

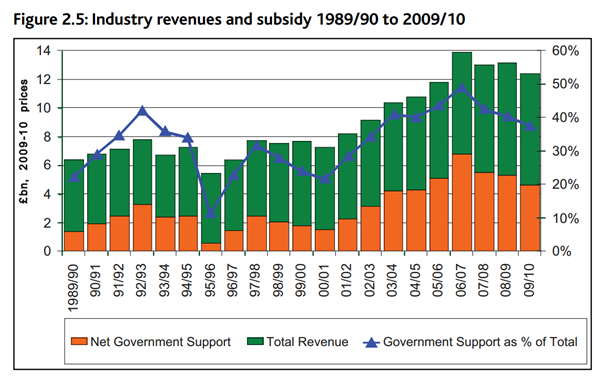

Incredibly, privatisation has not even reduced the dependency of the railway network on government subsidies. These subsidies have actually increased in both relative and absolute terms– and the long-term trend is that they are continuing to increase. Taxpayer subsidies are now around three times higher than they were before privatisation took place: around £5bn of the £11bn costs come directly from the state. As the McNulty report concludes: taxpayers are “manifestly not receiving” a “fair deal”.

So, we have a railway industry of growing importance to the economy, with soaring fares, decreasing inefficiency and an increasing dependency on the government for subsidies. Nobody could call this model a triumph for privatisation. It’s worth asking why the privatisation has been such a failure.

Why has Privatisation Failed?

It is time for the UK to look again at what is best for the railways. The mistakes of the 1990s should not be repeated…

Adam Smith Institute, whose ideas first inspired railway privatisation in the 1990s

Although even Margaret Thatcher had considered privatising British Rail a privatisation too far, John Major’s Conservative government promised privatisation in their 1992 manifesto, and after winning the election found themselves in the unfortunate position of actually having to implement it. In the end, the government chose to follow the advice of the Adam Smith Institute which, influenced by a staunchly pro-market ideology, was convinced that breaking up the “vertical integration” of British Rail would improve efficiency by allowing internal competition within the service.

The government placed Railtrack (a non-profit company) in charge of infrastructure, track and signalling, whilst profit-making Train Operating Companies (First Great Western, Greater Anglia, Virgin etc) rent the use of the track from them. Railway operators have to hire their rolling stock from three newly created Rolling Stock Leasing Companies (ROSCOs), largely owned by banks. The Adam Smith Institute first recommended seven, then twenty-five separate passenger railway franchises as a way of maximising revenue. Ultimately, British Rail was broken into more than 100 distinct companies, with most relationships between the successor companies established by contracts, and some through regulatory mechanisms.

This overly complex system has led to managerial chaos in Britain’s railways. There is widespread duplication of functions, which has inevitably resulted in a far more bureaucratic system: “backroom staff” have increased by 56% since privatisation. With the service vertically fragmented, strategic decision-making is an impossibility; companies controlling different parts of the service often have different and contradictory incentives. To quote transport expert and author of The Great British Railway Disaster, Christian Wolmar,

A senior Japanese railway manager, who like all his colleagues was appalled at the way we run our industry, put it another way: ‘How can the railways make the right investment decisions on say, signalling and track separate from the person in charge of operations or purchase of rolling stock?’ An irrefutable point.

The anarchic structure also goes a long way towards explaining the exorbitant costs and woeful inefficiency of the rail system. Each company along the supply chain must pay dividends to their shareholders, as well as hiring other companies for almost every process. Train companies need to pay leasing companies to hire rolling stock, and rail companies to use the railway lines. There are profit margins involved in each layer of contractors and sub-contractors adding to the costs of the system. Moreover, as with PFI (as I mentioned in an earlier post), government uses the private companies as a method for keeping its debt off the balance sheets.

The brevity of the contracts leaves operators without any incentive to invest for the long-term. Instead they see an opportunity to make quick profits at the taxpayers’ expense. As Julian Glover points out: “That’s why station car park charges keep going up but it has been two years since the last order for new trains.” In the rigged market that is operating, firms are often able to simply walk away from contracts rather than face losses, as First Great Western did last year. Stagecoach was able to demand £100m in extra effective subsidy from the government just to keep its contract. Clearly the system represents a huge case of market failure.

According to the ASLEF general secretary, Mick Whelan,

Added together these represent a cumulative, conservatively estimated cost to the taxpayer of more than £11b of public funds or around £ 1.2b a year. If these wholly unnecessary costs were eliminated and the resultant savings invested in reducing fares, it could deliver an across-the-board fare cut of roughly 18%.

There is now almost universal agreement that the method of privatisation used by the Major government was a disaster: even the Adam Smith Institute has admitted this. But there is not universal agreement on where to go next, with many advocating nationalisation. The Adam Smith Institute, John Redwood and the Libertarian Alliance all believe that instead the answer must lie in further privatisation.

Is Further Privatisation the Answer?

The Adam Smith Institute argue that the railway network is not truly privatised at all. Not only do the railways depend on private subsidy for almost half their income, political control over the strategic direction of the railways remains very strong, as shown by the recent Coalition decision for £10bn in capital investment. They argue that the original privatisation method they had recommended did not go far enough; to improve efficiency the railways need more privatisation.

Indeed, although the fragmentation imposed on railways was inspired by a belief in competition, it was a highly artificial structure. The original Victorian railway entrepreneurs ran almost fully self-sufficient companies, even down to the manufacture of the steel for the rail lines. John Redwood and the Adam Smith Institute suggest costs could be lowered by allowing the train operating companies to buy Network Rail assets, simplifying the system and allowing some degree of strategic co-ordination by train line companies. Meanwhile, they advocate removing restrictions on fare levels, to tackle overcrowding, and allowing companies to close loss-making lines.

The ASI are certainly right that a simplification of the system would reduce costs. Japan’s privatised rail system is among the best in the world, and receives only a little public subsidy. However, the fundamental problems causing high fare prices would not be solved, and closing loss-making lines could create even more problems, both to rail lines and the wider economy.

British rail prices are so high, in large part because the rail lines form an effective natural monopoly. There is no realistic room for competition between different providers, without entire stretches of rail track being doubled up (as happened at great cost in the late Victorian and Edwardian period). Without effective competition, rail companies have little restrictions (except direct government caps) on how much they can charge. As Will Self memorably put it:

The fundamental mistake – and there were many mistakes about the privatisation of the rail system – but the most fundamental mistake was rail travel, your journey to work, is not a fungible good and that means it cannot be exchanged for anything else. You can’t get to Guildford station and think: ‘Oh I won’t go to work in London today. I’ll go to Mars on this new rocket train that’s been provided by this splendid private company’.

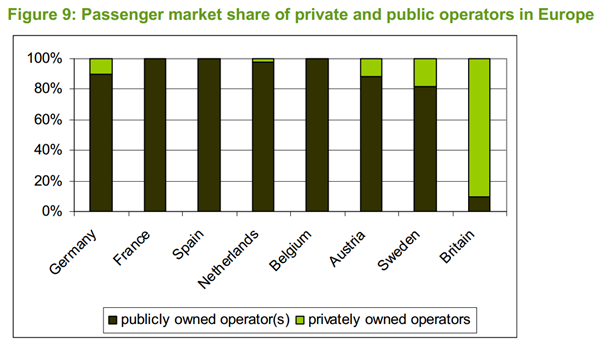

Every other Western European has a nationalised or effectively nationalised system, and has lower rail fares than the UK.

(Ironically, many of Britain’s rail lines have now been bought up b the nationalised rail networks ofother countries. Deutsche Bahn owns Arriva Trains, and the UK’s largest freight company, Schenker Rail. The Netherlands State railway is a joint owner of Northern Rail, Merseyrail and the Greater Anglia franchise.)

Although simplifying the operating structures would help to lower costs, it wouldn’t solve the fundamental problem with Britain’s rail prices, which are inherent in any privately run natural monopoly, such as railways.

The Adam Smith Institute accepts that prices would rise, and sees this as desirable, to cut over congestion. Yet increasing rail fares would have a shock effect on the rest of the economy, which increasingly relies on rail. With rail transport becoming increasingly important, higher prices can only be seen as a bad thing for the economy.

Closing unprofitable rail lines could also prove to be harmful for the overall railway network and economy. In the 1960s, the Beeching reports attempted to cut the losses of Britain’s rail system, advocating the closure of around a third of the network. The closures failed in their primary aim, achieving only £30million in savings, whilst overall losses ran at £100million per year. The branch lines that were closed saw little use, but they acted as feeders to the main lines. When the branches were closed, the main lines lost much of their traffic. Thus even unprofitable lines were important to the overall railway network, and the overall economy. As a result of closures aimed at increasing profitability, the entire rail system was damaged, and its usage fell.

Removing large swathes of Britain’s railway infrastructure also turned out to be extremely short-sighted. Many of the closed routes would now be heavily used. The Settle-Carlisle Railway as threatened with closure, reprieved and now handles more traffic than ever before. The Great Central Main Line closed 28 years before the opening of the Channel Tunnel rail link, which would have seen it become a major freight route across the UK. It will be replicated in part by HS2. The Association of Train Operating Companies want a total of 14 of the closed lines reopened.

In the area I live, major railway line closures took place in the late 1990s. Watford Junction station provides the easiest and fastest route into London. But Watford Junction is almost impossible to travel to from the surrounding towns: the old rail lines connecting it to Watford High Street, Watford West, Croxley Green (and in turn the many nearby stations on the metropolitan London Underground line) were closed, and the routes of the old rail line lie disused. Having realised that these cuts were short-sighted, the government is now investing to largely undo these changes, with the Croxley Rail Link, due to be completed in 2016.

Privatisation would almost certain lead to further cuts to Britain’s railway network, at a time when it is of increasing economic importance, and lead to higher fares. Both would damage the overall economy. It simply doesn’t make sense to hold a natural monopoly such as the rail lines in private ownership. Public ownership would bring obvious advantages, if viable.

Is Renationalisation Viable?

The think-tank Transport for Quality of Life recently published a study on Britain’s railways, where they concluded renationalisation was both affordable and feasible. It was this report that recently led Labour’s Maria Eagle to reconsider the issue.

Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling had argued that renationalisation would cost the government at least £22 billion, on top of the costs of putting the railway companies’ debts in the balance books. However, Transport for Quality of Life argue that railway franchises could gradually be renationalised by the state at close to zero immediate cost. The easiest approach would simply be to reacquire the franchises as contracts expire or companies fail to meet the conditions. Network Rail would be even easier to nationalise, as it has no shareholders and is already non-profit. The only associated costs would be putting its £24 billion debt on government balance sheet as public debt- although this debt already exists and is already in effect owned by the public. Overall, Transport for Quality of Life estimate these changes would save £300million per year, due to the government’s superior credit rating, and the increase in efficiency by simplifying the organisations.

Transport expert Christian Wolmar argues:

In fact, what New Labour refuses to let on is that the railways are effectively largely publicly-owned anyway. Network Rail, which owns the infrastructure, is a company without shareholders that is dependent on government backed debt (to the tune of £20bn), for its survival. It receives billions in annual grants direct from government and is, to all intents and purposes, a state-run enterprise.

In fact, with Network Rail already in public hands, it would cost nothing to bring back the railways under public control if the train operators handed back the franchises either when they get into financial difficulties or when their terms expire.

Such a decision would be politically difficult- governments have shown themselves extremely reluctant to be honest about the real levels of public debt- as shown by the continued use of PFI. However, the real practical difficulties involved in the renationalisation would not be huge- the government continues to exert a large amount of control anyway, and the costs would be close to zero.

Nationalisation is back on the Agenda

Renationalisation would not only save government money, it would also increase the efficiency of the rail network, allow for more strategic planning and allow government to lower the fees. This is the obvious way forward, if we want a better rail network. It makes little sense for a natural monopoly like the railways to be held in private hands. Privatisation has led to fragmentation, chaos, soaring prices, and an increasing dependence of state subsidy. Further privatisation would only lead to even higher fares, and the closure of many lines, that whilst unprofitable in themselves, are essential to the wider economy.

Opinion polls have consistently shown a clear majority -including a plurality of conservative voters- supporting renationalisation, and it has long been party policy for the Greens and Plaid Cymru. The fact that Labour is once again talking about renationalisation is a positive sign. With the British economy ever more dependent on the railways, its time once again to call for nationalisation.

http://symmetrybreaks.wordpress.com/2012/07/18/time-to-renationalise-the-railways/